- Home

- Dana Middleton

Open If You Dare Page 2

Open If You Dare Read online

Page 2

If you’re reading this, it says, I’m already dead.

2

ALLY IS usually the brave one. She has four older brothers and that’s made her tough. But she’s the one who inches back while Rose leans forward and whispers, “Go on.”

Further down the page, below that ominous line about somebody already being dead, there’s more writing. It looks like a poem and I read it out loud.

R.D. is not alone anymore.

Because now I’m a dead girl, too.

I could have mailed this (I could have!) but

I’m not going to make it easy for you this time.

You know her address.

Where feathers are hard.

Keep following the clues!

Because he’s still out there.

“Where feathers are hard?” I repeat quietly. “I’m a dead girl, too…?”

“What does that mean?” Ally asks. I look up at Rose and Ally’s gaping faces.

“I don’t know. It’s a clue.” My eyes search the box for help. “Look at this.”

“Look at what?” Rose asks nervously.

“No bones,” I say and reach inside. I pull out a ring—a silver one with an oval black stone on top.

Rose tilts her head, examining it as Ally says, “Looks haunted.”

I put it on my ring finger anyway. It fits. And I realize: “This ring—”

“—belonged to a kid,” Rose says, finishing my thought. I take it off quickly.

“Somebody like us.” Ally shifts forward again. “Let me see.” I give her the ring and Ally glides it onto her finger. Holding up her hand, she studies it like it’s a precious diamond. “Who would wear a ring like this?”

I’m wondering the same thing, when the black stone turns deep purple right before our eyes.

“Eek!” Ally cries, flinging the ring off like it’s a snake coiled around her finger. The ring lands with a CLINK back in the box and we watch it magically turn black again.

“It is haunted,” I say.

“Relax,” Rose says, picking it up again. “It’s a mood ring.”

“What’s a mood ring?” I ask.

“A ring that changes colors with your mood.” Rose puts it on her finger and we watch it turn blue. “Didn’t know they had these back in 1973.”

“Yeah, when it belonged to a dead girl,” Ally says.

“Good point.” Rose says, promptly dropping the ring back into the box again. It lands on a small rectangular card tattooed in black ink.

I pick the card up and hold it to the light. It feels thick between my fingers. “I think it’s a ticket.”

“A ticket?” Rose reaches out. She takes the ticket and she examines it like it’s a relic from a museum. “Allman Brothers Band. The Omni Coliseum,” she reads. “From June 2, 1973.”

“That was a long time ago,” Ally points out.

At the top of the yellowed notebook paper that’s resting on my knee, I see the date that’s written in girl’s handwriting again: June 28, 1973. “Look, this note was written in June 1973, too. Less than a month after the … whatever Brothers concert.”

“So?” Rose asks.

“So … has this been buried here the whole time?” I feel like I am traveling back in time to 1973. I count back on my fingers. “That’s over forty years ago.” I don’t think my mom was even born yet. “What’s that on the back?”

Rose turns over the ticket. “Horrible handwriting. Mrs. Allot would flunk her out of English.” She gives it back to me. “You try.”

“I think it says Ruth … Ruthie … Dal … Del … Gado.”

“Ruthie Delgado?” Ally’s face scrunches. “Who’s she?”

I look at them, deadly serious. “I think that’s what we’re supposed to find out.”

* * *

When I wake up, it’s after nine. I smell bacon.

Sliding off the book that’s been sleeping on my chest, I slip out of bed. From downstairs, I can already hear Zora. Talking, talking, talking. Walking past my corkboard of selfies, I spy the one Rose took of us in front of the Gillans’ house three days ago. It looks like we’re smiling except for our eyes. Tiny cracks of uncertainty are now living there, cracks that will surely grow bigger by August.

Our old eyes stare back at me from hundreds of other selfies on the board. Ally, Rose, and me at a violin recital. Us together at a baseball game. Us at the pool. During a field trip. At the local library. There’s even one with us and the librarian, Mrs. Thompson.

I head downstairs in my pajamas and lean against the kitchen door. Dad is flipping bacon in the skillet as Zora sits on the counter talking to him. It’s the first Monday of summer break, so Mom must have left for work already. The best I can decipher, Zora is recounting a SpongeBob episode, line by line. My dad nods and makes interested noises like he’s into it.

“Birdie!” Zora jumps off the counter, runs over, and gives me a hug.

“Morning,” Dad says and smiles.

“Morning, Dad.”

“Birdie, Birdie, Birdie,” Zora says, bouncing up and down. “Look what we got from the basement!” She points at the big chalkboard on wheels that’s set up behind the kitchen table. Oh, great.

“I see it.” I can hardly contain my excitement.

“We were waiting for you to make Mickey pancakes,” Dad says.

“Mickey pancakes!” Zora yells. “Can I help?”

“Sure you can, Ace!” Dad says, and Zora pulls over the step stool as Dad pours batter mix into a big bowl.

I plop into my chair at the kitchen table and stare at the empty chalkboard. Of course Zora is excited. This single chalkboard represents everything that’s right and wrong about Zora and our dad.

It’s called mathematics.

Don’t call it math. Not in our house. My dad is a high school mathematics teacher. He teaches calculus, trigonometry, geometry, and algebra. He knows it all. And loves it all. He thinks it’s very important for us to love it, too. So every summer he sets up Super Summer Mathematics Camp.

Zora is the number one participant. It’s every day with the two of them. I am required to attend two mornings a week, and since I do it, Rose and Ally sometimes come. It’s only for an hour and they like my dad. Or they like me. I don’t really know why they do it. I’m just glad when they do.

I am not gifted in mathematics. I would prefer reading a book … or solving a puzzle.

My mom is a scientist who likes books but not as much as she likes science. Zora is strangely gifted in both fields. Not sure she can read but she can tell you the square root of three zillion and fourteen without using a calculator. Sometimes I think I was born to the wrong family because I’m so different from them.

“Zora!” I call out. Sheepishly, she looks my way. “What’s he doing down here?!”

“You were sleeping and he was lonely.”

I roll my eyes and pick up Peg Leg Fred, who is propped up on her chair surrounded by little metal airplanes. Peg Leg Fred is my oldest stuffed animal. He’s a polar bear who lost his leg, so Mom and I made him a special bear leg prosthetic, which made Dad call him Peg Leg. “He’s not yours.”

“I know.”

“Come on, Birdie. Loosen up,” Dad says as he helps Zora crack an egg over the pancake batter. “In the immortal words of Alice Cooper, ‘School’s out for summer.’”

“Who’s she?” I ask.

Dad shakes his head. “It’s a he. And Zora didn’t hurt Peg Leg.”

I hug Peg Leg to my chest. “Whatever,” I whisper but not quietly enough.

“Elizabeth.” Dad only calls me Elizabeth when he’s not happy with me. My real name is Elizabeth Jade Adams, but Dad started calling me Birdie when I was little.

“Sorry,” I say. Our eyes meet. “Really.”

He nods. “Okay, then.”

Peg Leg sits on my lap while we eat Mickey pancakes. I have three. Zora and I pour more syrup on our bacon than on the pancakes. Dad thinks that’s gross. We got that from Mom.

<

br /> “So, exciting news, girls,” Dad says as he eyes the chalkboard. “This summer is going to be all about…”

Zora leans forward in anticipation.

“Algebra!” he says.

“Yay!” Zora claps. Her eyes light up as she turns to me. “Birdie, you’re going to love it!”

How did I not know my seven-year-old sister was already doing algebra? No wonder she’s starting a special school next year.

Dad forks a stack of Mickey ears into his mouth, then continues. “First, we’re going to tackle variables, which we sometimes call…”

“Vampires!” Zora cries.

“And then from vampires, we’ll go to…”

I try to concentrate on my pancakes while pasting a smile on my face so I look like I care about the nerd-talk coming out of Dad and Zora. I really do try hard. It’s their first day of summer as well, and I know this means a lot to them. I try to look interested. I try to nod at the right places. I try to keep my eyes open but I’m afraid they’re glazing over. Because what I’m thinking about is much more important.

The dead girl.

I can’t get her out of my head. Ever since we found the box, I’ve been thinking about Ruthie Delgado and the other girl, the one who wrote the clue and buried the box and might be dead, too. Because as I read and reread the clue all weekend, it’s been sinking in what it really means.

Somebody killed Ruthie Delgado. That somebody was a him. And when the other girl went after him, he killed her, too. This is a story of two dead girls. And even though it was a very long time ago, it’s up to us to find the next clue so we can solve what happened to them.

“Birdie, you’ve been staring at your pancakes for five minutes. Did you hear any of that?” My dad’s voice pulls me back into our kitchen. Back to our pancake breakfast.

I look up, startled. Because, no, I didn’t hear any of that.

He grins at me. “First day of summer gets a pass. Come on. Help me with the dishes.”

3

I CAN’T help it. It bothers me that she doesn’t answer, that she doesn’t wave back.

“Hi, Mrs. Hale,” I call out again. But nothing. So why do I keep trying?

After breakfast, I hung out for the first Super Summer Mathematics Camp with Dad and Zora then peeled off for the pool to join Rose and Ally there. Other than Ally’s baseball game on Saturday, it’s been family time all weekend.

Mrs. Hale lives down the street from us, between my house and the pool. Or between my house and Rose’s house. It’s practically the same thing. I pass Mrs. Hale’s house almost every day in the summer, usually wearing my summer uniform: bathing suit, shorts, and sneakers to protect my feet from the burning asphalt.

Mrs. Hale’s house is old and covered in green ivy. There’s a brick chimney, a shingled roof, and massive tree limbs hanging overhead. The entire lawn is all bushes and flowers and plants.

Mrs. Hale is digging in her azalea patch, her back turned to me as I go by. She’s wearing jeans and sneakers, her white hair pulled back in a tight old-lady bun.

“Hi.” I try one more time, but she keeps pulling up weeds (or something like that) and doesn’t acknowledge me in any way. Rose thinks Mrs. Hale must be mean. Ally thinks she’s crazy. I’m not exactly sure what I think yet.

Maybe I keep trying because I’ve lived in this neighborhood my whole life and Mrs. Hale has been here much longer than that. And she lives in that big house all by herself.

Sometimes, when our eyes do meet, she actually gives me a small nod or a little wave, but somehow it feels reluctant. Like she’s not so sure about me. And I can’t help but wonder …

Because my mom is white and my dad is black. Our neighborhood is mostly white and so is my school. I don’t think about much about it. Neither do my friends. We’re just who we are. Zora and I look alike, a perfect blend of both our parents. Dad calls us his mocha Frappuccinos. Mom calls us the future.

Secretly, I wonder sometimes if Mrs. Hale is one of those old southerners who isn’t ready for our kind of future yet.

* * *

“Maybe we should go to the police,” Ally says.

We’re sitting on the side of the pool, feet dangling in the water, our skin quick-drying in the blazing Georgia sun.

“They probably have more important things to do than go chasing after some random clue from some yet to be determined reliable or unreliable source,” Rose says.

I eyeball Rose, realizing the curiosity she filled up on when we discovered the box has been seeping out of her like a slow leak from a three-day-old helium balloon. “You don’t know she’s not reliable,” I say.

“You don’t even know she’s a she,” Rose fires back.

“You saw the handwriting. It was cursive and neat and no boy would write like that.”

“Okay,” she says, “but how do we know it’s for real. It could be a hoax. Some kind of game someone was playing.”

“It’s not a hoax,” I say emphatically. “I think the dead girl—”

“Which one is the dead girl again?” Ally cuts in. “I’m getting confused.”

“I think they’re both dead!” I say, louder than expected.

“Calm down, love,” Rose says, sounding British and a bit superior. I hate it when she does that.

Lowering my voice, I continue. “Okay, listen. Just so we can keep this thing straight, the dead girl is Ruthie Delgado. She was the one who was going to the concert but didn’t come back.”

“Check,” Ally says.

“So what do we call the other girl?” I ask.

“The nutty one,” Rose says with a grin, which I reward with my pointy elbow in her arm.

“How about the Girl Who Buried the Box?” offers Ally.

“Groan,” says Rose. “I’m not saying that mouthful every time.”

“Yeah,” I say. “We need a name.”

“Like what?” Ally asks.

“I don’t know.” So I think. This girl was trying to solve a mystery. She was on the trail of a murderer. What do you call somebody like that? “Girl Detective!” I suddenly blurt out. “You know, like Nancy Drew?”

“Who?” Rose asks.

“Nancy Drew, comma, Girl Detective. Don’t you ever read?”

“Not since the Internet was invented,” Rose says. Taken literally, that means she’s never read a book in her entire life.

“You’ve seen them on my shelves. The Nancy Drew mysteries. It’s a series. Like Harry Potter but a ton more.” I’m met with blank stares. “My mom gave me her books from when she was our age. Nancy Drew’s a teenager who solved mysteries long before our Girl Detective came along.”

“Oh, you mean like Sherlock Holmes?” Rose asks.

“Exactly like him, except for the hundred ways that they’re different.”

“I like calling her Girl Detective,” Ally says. “Makes her sound official.”

Rose nods. “I could go with that.”

“Yeah, me too. Girl Detective it is.”

“Great!” Ally says, kicking her legs and making a splash. “Now we can go to the police.”

“I think that was the whole point of the clue,” I say.

Ally looks at me. “What do you mean?”

Since the box has been hiding under my bed all weekend, I’ve had plenty of time to memorize the clue. “Because Girl Detective said, and I quote, I could have mailed this (I could have!) but I’m not going to make it easy for you this time. Which means to me that she told someone official and they didn’t listen to her.”

“How do you know she told someone official?” Ally asks.

“I don’t for sure, but if I were Girl Detective, it’s what I would have done.”

“You would have told the police?” Rose asks, like she doesn’t believe me.

“Yes, I would have. And I think she told the police. But they didn’t listen.”

“Even if she did, that was the 1970s police,” Ally says. “Police would pay attention now.”

Tha

t’s not exactly what my dad would say but maybe she’s right. “But if we tell the police—”

“—the police will tell our parents,” Rose continues. “Could you imagine what my mom would say?”

“So let’s just tell a parent,” Ally says.

“The General?” I ask.

“Well…,” says Ally. We call Ally’s mom the General. Not to her face or anything. Just to ourselves. Mrs. Lorenz (the General) runs their household like a military commander. She works all week as a paralegal secretary downtown, so the kids have to fend for themselves a lot and really help out at home. “Maybe not her. I was thinking more about your dad.”

“If we tell my dad, he’ll want to know where we found the clue. And the box,” I say. “And then we’ll be busted about the island.” My parents trust me. And mostly they don’t worry about us as long as we stick together. But there are certain rules. Like: Stay in the neighborhood. Don’t go past the pool. If we told them about the island, we’d be banned from there forever.

Ally sighs. “So…”

“Yeah, so,” echoes Rose.

A whistle blows, and my eyes turn to the lifeguard chair elevated between the regular pool and the deep end. Mrs. Franklin has been our lifeguard for as long as I can remember and she runs the pool area like the General runs Ally’s family. Even though she’s sheltered under a big sun umbrella, her white skin is already on its way to leather brown. A familiar dab of zinc oxide streaks the bridge across her nose.

“I tried to google Ruthie Delgado,” I say. “To find out where she lived and stuff.”

“And?” asks Rose.

“Nothing. Couldn’t find anything. Like she’s a ghost or something.”

“A dead ghost,” Ally says gravely.

“I found the Allman Brothers, though.”

“Yeah?” says Rose.

“Yeah. They were a rock band. From Jacksonville, Florida. Gregg and…” I struggle to remember the other one’s name. “Duane, I think. Yeah, that’s it. Duane Allman. The band moved here—”

Ally brightens. “To Georgia?”

I nod. “They had super-long man hair and weird mustaches. I’ll show you the pictures. One of them died in a motorcycle accident, though.”

Not a Unicorn

Not a Unicorn The Infinity Year of Avalon James

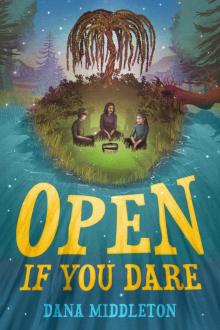

The Infinity Year of Avalon James Open If You Dare

Open If You Dare