- Home

- Dana Middleton

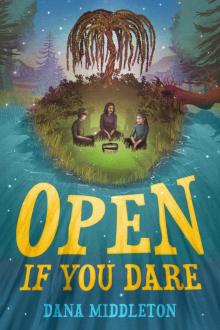

Open If You Dare Page 11

Open If You Dare Read online

Page 11

When the last long note ends, everyone cheers. Rose smiles. Then looks at her mother defiantly.

As the sun goes down, the fireworks display from the pool begins. Everyone crowds into the Ashcroft’s front yard and takes a place in a lawn chair or stretches out on a blanket in the soft grass. Little kids crawl into laps as the colorful show erupts in the night sky. Rose, Ally, and I sneak to the upstairs porch off Rose’s parents’ bedroom and watch by ourselves. We see Rose’s brother, Simon, walk around the corner of the house with Ashley. I see Zora, sitting on Dad’s lap, pointing to the sky.

“We’re going to visit my grandma the week before school starts,” I say. I’ve been meaning to tell them for a while now, but there hasn’t seemed to be the right time.

“In Chicago?!” Ally exclaims.

“You mean before I leave?” Rose says.

“Yeah.”

“But why? They know I’m moving, right? Don’t they understand we need all of this summer?”

“I guess not,” I say and feel a wave of sadness run between us.

“Can’t you talk them out of it?” Rose asks.

I shake my head. “Tried. It’s kind of a done deal.”

“Oh,” murmurs Rose.

“Gosh, Birdie,” says Ally.

Quietly, we stare up at the sky. I’m relieved when Rose breaks the silence. “They don’t do this where I’m going.”

“What, no fireworks?” Ally asks.

“No. No Fourth of July.”

“Oh.” Ally sighs.

And I realize this will be our last Loser’s Day party together. I may never enjoy the Fourth of July again.

“Will you have to wear a uniform at your new school?” Ally asks.

“Probably. Mum will be thrilled. She loves to watch me suffer.”

I spot Mrs. Ashcroft among the crowd in the front yard. Rose’s mom has always been nice to me, except after the stink bomb incident. But that seems to be behind us. I try and think when it started getting so tense between Rose and her mom. It can’t have always been this way.

“My dad’s moving…” A loud burst of fireworks drowns out Rose’s voice.

“What?” Ally asks.

“Next weekend. My dad’s moving.” Rose says it loudly so we can hear, her eyes locked on the combusting sky.

It’s only July and it’s getting real now. In less than six weeks, Rose will be gone. In less time than that, I will be saying good-bye to her. Then someone else will be living in this house. And we’ll be starting school, each of us, alone.

21

THE FIRST thing I learn is that Smith is a very common last name.

Ever since the fabric store, I can’t get it out of my head that the father of murderous Martin Smith is living in a nursing home in Decatur. So I make a list of nursing homes I find on the Internet, sneak away to my room with the landline, and start calling.

The second thing I learn is that people who answer nursing home phones are, by and large, not so helpful.

But I keep calling. Each time I ask to be connected with Henry Smith. The first time I think I find him, I’m connected to a Harvey Smith, who sounds really mad that I made his phone ring. The second time, I end up talking to a man named Paul Smith, who is very pleasant. The third time, I get very excited because I reach an actual Henry Smith. But it turns out to be Henry Smith, retired lawyer, not retired butcher.

Finally, I hit the jackpot. When I ask for Henry Smith at the Shady Hills Retirement and Nursing Home, the receptionist says, “Yes, hold please,” and I hold. Butterflies gather in my stomach as my call is transferred to Henry Smith’s room. A lady answers the phone. “Hello.”

“Is Henry Smith there?” I ask.

“Yes,” she says. “But he’s resting right now. May I help you with something?”

“Are you his wife?”

“No, I’m Clara,” she says, a laugh in her voice. “I’m his nurse.”

“Is this Henry Smith of Smith and Sons? I just want to be sure. I mean, is this the Henry Smith who used to be a butcher?”

She doesn’t respond for a moment, then says, “Yes, I think so. I think Mr. Henry was a butcher. Can I take a message?”

I don’t know what to say. I’m prepared to ask questions but not to answer them. “No,” I say.

“Okay, but I’m sure he’d like to know who you are. He doesn’t get many calls these—”

“Could we visit him?” I blurt out.

“Oh, well, it depends. I think I’d need your name for that.”

“Sure,” I say. “I’ll call you back.” And I hang up the phone. I just hang up the phone. In real life, I would make a terrible investigator.

* * *

The next day, I’m sitting at the kitchen table with Ally, Rose, and Zora at Mathematics Camp. But, today, it’s not just mathematics. Today, we are cracking combinations.

I mean for lockers.

When you go to middle school, you get a locker for the first time. Lots of kids have locker anxiety. It’s practically an epidemic between elementary and middle school. As a teacher, my dad knows these things, so he’s getting us ready.

Each of us (even Zora) has a combination lock in front of her on the kitchen table.

“I don’t even know if they have lockers in England,” Rose says.

“But if they do, you’ll be prepared,” Dad says. “And preparedness is one of the key elements to creating calm under pressure.”

Rose shrugs her shoulders. I’m so glad she resists a “whatever.”

“Here are your combinations.” He hands each of us a small sheet of paper. I unfold mine and see three numbers inside: 15–22–4.

Dad explains how to turn the revolving lock: two revolutions to the right to the first number, one revolution to the left to the second number, and then straight to the last number.

“Done!” Zora’s lock clicks open.

Even Rose, who’s been giving us her best I don’t care attitude, focuses harder. No one wants to get beat by a seven-year-old!

Click. I pull my lock open. So does Rose. We look at Ally, who’s tugging on her lock trying to open it when clearly she’s put in the combination wrong. My dad comes up behind her and starts helping.

My dad is very patient with Ally. He’s the kind of teacher who makes you think you’ve figured it out all by yourself, when actually he’s walked you through every step. After Ally turns the lock carefully to her third number, she gazes up at him. Dad smiles at her and nods. Ally pulls the lock. When it opens, her face floods with relief. “Thanks, Mr. Adams,” she says.

“You’re welcome, Ally. Now close your locks, and let’s do it again.”

Sometimes I think Ally purposely gets things wrong to get extra attention from my dad. It doesn’t bother me. Really. I’m not even sure Ally knows she does it. But sometimes, when she just can’t understand a mathematics problem (and it’s really not that hard), it makes me wonder. Ally wants a dad and I’ve got a good one, so I get it. Even though sometimes I have to remind myself that it’s important to be a good sharer.

“Birdie?” I look up. Everyone’s finished opening their locks but me. “You want to join us?”

“Yeah. Sure, Dad.”

While we’re doing combinations, it starts to rain. Slow, easy drops at first, but soon it’s pelting. I watch Rose’s combination work slow as her eyes keep darting to the kitchen window.

“I read it rains all the time in England,” I say.

“Great. Another reason I don’t want to go.”

“I don’t know if anyplace rains like Georgia in July,” Dad says. And as if on cue, a burst of thunder hits our roof like cannon fire. “Whoa! That was a big one.” I tense up as Rose slips under the table. Dad looks down at her. “Rose, it’s a scientific fact that thunder can’t hurt you.”

“But lightning can.” We look at Zora like we can’t believe she just said that. “Well, it can,” she says.

“I guess no swimming today,” Dad says.

“Th

at’s okay,” I say. “We can hang out in my room.”

“Me too?” Zora asks excitedly.

“No, Zora, let’s stay downstairs,” Rose says. “We could watch a movie or something.”

“Yay!!” Zora careens down the stairs like she’s won the lottery. “Which one?” she yells back to Rose.

“Whatever you want.”

I eyeball Rose. “Are you kidding?”

“I want to watch a movie, all right?” she says defensively, when we all know she won’t go upstairs because of the thunderstorm. I can’t help but think, Why today? Because all I want is for us to go up to my room and start planning our secret mission to Decatur. Which I haven’t told them about yet.

As Frozen starts on TV downstairs, I ask Ally to come upstairs with me. As we climb the stairs, she asks, “Do you have to wear that ring?”

I look down at Girl Detective’s mood ring on my finger.

“It’s not haunted.” I hold it up, currently shining green.

“It’s still weird.”

“Think of it as an artifact,” I say. “From another time.”

“Great.”

In my room, I pull the list of nursing homes out of my desk drawer and show it to Ally. Rose and I already told her about our excursion to the fabric store. She knows about Henry Smith. But neither one of them knows I’ve found him.

“Hmm,” she says after I’ve given her a full update. “So you want to go all the way to Decatur and talk to some old guy in a nursing home who we’ve never met before?”

I nod. “Yes, I do.”

Honestly, I’m expecting her to say that’s ridiculous and there’s no way we’re following that trail. But that’s not what happens. She just looks at me and says, “We can catch the bus by my house.”

22

“I VOTED for president this morning. Did I tell you that?” he asks. “This is a very important election. Can’t have a liberal commie in the White House. That’s the way we ruin this country.” He shakes his head. “Young people. Don’t understand this voting at eighteen. Who says eighteen years old is old enough to vote?! You’ll understand one day. Can’t have a liberal commie in the White House. No, sir.”

Henry Smith’s eyes are aimed at me. Like I can vote or something. Like it’s actually an election day.

I look over at Rose and Ally sitting on the small couch against the wall and mouth, What’s he talking about?

Clara, the nurse, touches my shoulder as she pours Mr. Smith a glass of water. I’m sitting on the chair next to his bed. Because as Rose said, this was my big idea.

“Who’d you vote for this morning, Mr. Henry?” Clara says loudly. She hands him the glass of water and hovers like she’s waiting for him to spill it.

“Nixon, of course!” he booms. “Who else would I vote for? Not that liberal commie, McGovern. I’ll tell you that!”

“Nixon?” I ask, confused.

“Richard Milhous Nixon,” he states emphatically. “Mark my words: By tonight, he’ll be elected to his second term as president of these United States. Going to go down in history as one of the greatest presidents we’ve ever had.”

We’ve studied lots of presidents at school and I don’t remember Nixon being at the top of any great presidents lists.

I turn to Rose. “What year did Nixon beat McGovern?” I ask and she pulls out her phone.

“1972! What year do you think it is?” Mr. Smith says.

“Now, let’s not get you agitated, Mr. Henry.” Clara takes the glass from his hand. “These girls were kind enough to come visit. And I’m sure their parents have already cast their ballots for Mr. Nixon this morning.” She winks at us. “Do you remember why they’re here?”

Mr. Smith looks at her blankly. In the half hour since we’ve been here, this is the third time Clara has asked him this. And this is the third time he doesn’t have an answer.

“These girls are here because you knew their grandmother when you used to have the butcher’s shop. They’re doing a report for school about how their neighborhood has changed over the years.”

At least this was the story we came up with on the bus ride over. Ally figured out the whole bus schedule. We were supposed to be at her house for the day because it’s Saturday and the General was supposed to be home but she’s really working. And Mark doesn’t care what we do. So we caught the bus on Ashford Dunwoody Road at 10:00 a.m., transferred twice, and reached Shady Hills Retirement and Nursing Home by 11:20 a.m.

At the reception desk, we acted like Mrs. Gates was Rose’s grandmother and that she asked us to visit her old friend, Mr. Smith. It was pretty lame but I guess they’re hard up for visitors at nursing homes. So after waiting several minutes, Clara appeared in the reception area and brought us to Mr. Smith’s room.

The room is dreary but painted yellow, I guess to make an effort. Mr. Smith lies in a hospital bed, propped up so he can see us. A TV is bolted against the wall and the sole window looks out over a parking lot.

“Have you been to my butcher shop?” he asks, brightening.

“Yes,” Rose says from the couch. “We went there the other day.” She neglects to update him on the fabric shop development.

“Everything running like clockwork, I suppose,” he says. “Can’t wait to get out of here and back to work again.”

“Rose’s grandmother says you have the best pork chops in north Atlanta,” I add.

“Just north Atlanta?” he says with a grin.

I shake my head, playing along. “No, I think you’re right. She must have said all of Atlanta.”

“Now that’s more like it.” His teeth are yellow but his smile is nice.

“Do you girls mind if I go check on Mrs. Landry next door for a few minutes?” Clara says quietly. “He won’t be any trouble and it’s sure nice for him to have the company.”

“What’d you say?” Mr. Smith calls out.

“I’ll be right back, Mr. Henry,” Clara says. “Be nice to the girls.”

We all watch Clara leave. I’m glad she’s gone, because we have important questions to ask. But as the room falls silent, I’m not glad she’s gone, too.

“Did you see Martin?” Mr. Smith finally asks.

“You mean your son?” I perk up in my chair.

“Yes. At the shop.”

I turn to Ally and Rose, then back to Mr. Smith. “How is your son?”

“Martin is a good boy,” he says, a twinge of sadness in his voice. “But I do worry. I worry about that boy.”

He should be worried about him: He’s a murderer! “Do you know who Ruthie Delgado was?” I ask him.

“Ruthie Delgado?”

“Yes. Did you know her?” I ask. “Did Martin know her?”

Mr. Smith leans up in bed. He doesn’t say anything but just looks at me. Like maybe he’s trying to remember something.

“Ruthie Delgado,” I say louder. “Your son knew her. I think something happened to her. Do you remember what happened?”

“I remember you,” he says, a fog lifting. “You. You asked me this before.”

“I don’t think so,” I say, but he doesn’t seem to hear me.

“About this Ruthie girl.”

“No, I wasn’t—”

“You. I remember you.” He’s staring at me like he’s in a trance. “Red hair. You had red hair. Is that a wig you’re wearing?”

I touch my dark hair. This is getting weird.

“I remember you,” he says again. “Why are you hiding your hair? Why are you trying to trick me?”

I don’t know what he’s talking about. “I just wanted to know about Martin,” I say nervously. “And Ruthie Delgado? What did he do to her? And then what did he do to the girl who came asking?”

“Martin!” he calls out. “Martin, she’s here again! I won’t let them hurt you, Martin.”

I look back at Ally and Rose, who are already standing, their shocked faces matching mine. My hair isn’t red. I’m not trying to trick him. And then it hits me. He’s not

remembering me. He’s remembering her.

He’s remembering some other twelve-year-old.

“Mr. Henry, calm down, now.” I jump to my feet as Clara sails back into the room. “It’s okay. You just got confused.” She helps him settle back in bed. “Maybe it’s time for a little rest.”

“I don’t know. I just don’t know,” he says.

I hover at the doorway and watch the fog reclaim him. Ally and Rose are already fleeing down the hall.

“There, there,” Clara says, pulling up his blanket. “It’s Clara, Mr. Henry. Remember me? Clara.”

He’s very still for a long moment, then asks, “Have I voted yet today, Clara?”

“Yes, you have. Voted first thing this morning.”

“Good.” He lifts his head and looks at me. “And thank you, Clara, for having your daughter come visit with me today. She’s nice like you.”

“She sure enjoyed visiting with you, too.” She pats his shoulder and says, “Just rest now. Just rest.”

It’s strange that he thinks Clara is my mother. Our skin is almost the same color but we look nothing alike. And she’s way too old to be my mom. After Mr. Smith closes his eyes, Clara walks toward me.

“He’s a nice old white man,” she says quietly. “But he doesn’t much remember progress, if you get what I mean.” She gives me a questioning look. “He didn’t say anything he shouldn’t have, did he?”

I shake my head. I see my white friends waiting down the hall and know Clara would never ask them that. “No, he didn’t,” I say.

“Good.” Clara gives me a smile. I look at my friends again and then turn back to her. Clara must know things.

“Can I ask you a question?”

“Yes, of course,” she says.

“Do you know what happened to his son, Martin?”

“Oh, Martin. Mr. Henry gets upset when people bring up Martin.”

“Why?”

“Well, because Martin died,” she said. “When he was young, too.”

“How did it happen?”

“I don’t know. Some kind of accident,” Clara says, then stops. I think she’s finished talking but she’s not. “I hear things, you know. Over the years you can’t help but hear what people say. I get the idea that Martin was a bad egg.” She pauses again and her eyes meet mine. “I’d bet dollars to doughnuts that boy met with trouble.”

Not a Unicorn

Not a Unicorn The Infinity Year of Avalon James

The Infinity Year of Avalon James Open If You Dare

Open If You Dare